Hugh’s choice of tree for last month’s demonstration was Casuarina or more precisely, Allocasuarina which are a favourite his. Commonly known as she-oak, Casuarina and Allocasuarina are in the same family but Allocasuarina are only found in Australia while Casuarina are found all over SE Asia, the Indian subcontinent and islands in the West Pacific Ocean. Hugh brought several trees (a couple trees in development and some others that were being refined) to answer the following questions:

- What are they?

- Why do they behave as they do?

- How do we deal with them as bonsai?

Casuarina, like all native trees, have to deal with very harsh conditions and poor soils so this makes them good choices for bonsai because they are used to tough conditions. Also, because they come from arid places where most trees don’t want to live, their form is often aesthetically pleasing reflecting the harshness of their habitats. In fact, Hugh’s first collected tree was an Allocasuarina. While there are many species of Casuarina, including 61 species of Allocasuarina (found mainly in the south), the main choices for bonsai are A. littoralis, A. torulosa and C. glauca.

A. littoralis is one of the most widespread species in eastern Australia and named for its growth near the coast. Known as the black she-oak, it has dark fissured bark which looks black at certain times of the year. It has smaller ‘needles’ (really scales) than the others but doesn’t throw branches if a bit weak.

A. torulosa, the rose she-oak or forest oak, is a sub-rainforest tree that grows just outside the main forest area and is endemic to Queensland and NSW. It has a corky light brown bark and thin green needles like a pine. Branches turn a beautiful copper colour in winter. Because A. torulosa grows in fire prone areas, it is more ephemeral and used to regenerating itself after a fire and so throws branches well. Because A. torulosa is a forest species, it needs a bit more water than A. littoralis. Foliage can be an indication of a tree’s strength; fine foliage probably means less robust while tough foliage indicates a better survivor.

C. glauca or swamp oak is also a native to the east coast from central Queensland to southern NSW and grows close to water as its name would imply. It is a fast growing, super strong tree that can reach 100 years of age in its natural habitat.

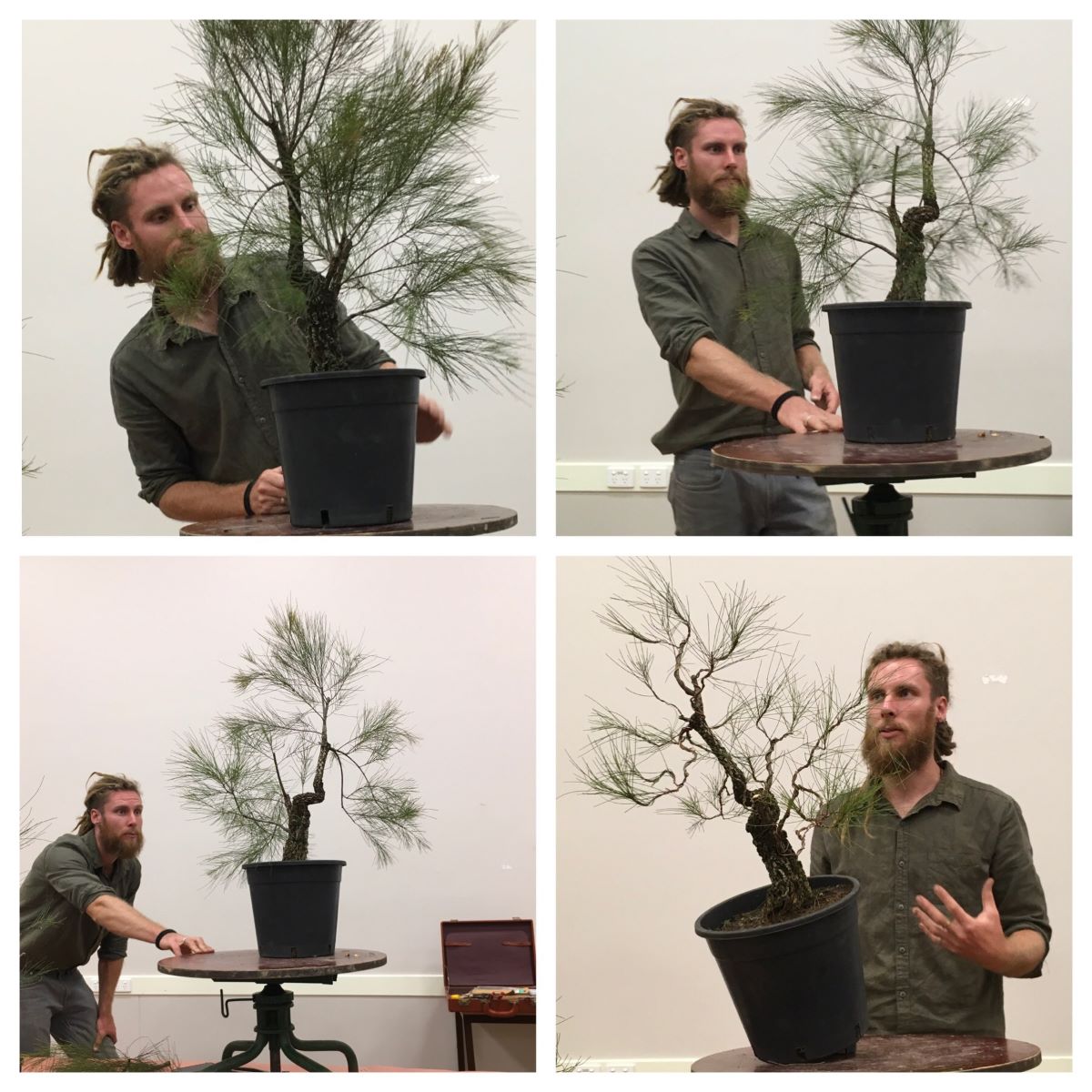

Hugh likes to start by ‘reading’ a tree, looking for its flaws and features and then choosing a path of action that will maximise the line of the tree (rather than focusing on a front at this point). This is much simpler on a nursery tree but more challenging when nature does the planning. This A. torulosa is six or seven years old and Hugh’s first thought is that the top needs to be reduced because it is straight and strong. This is a forest tree and as such needs to be softer, growing both upwards and outwards but with some ‘jazz’ to make it interesting.

The bend in this tree is its main design feature and so needs to be opened up; the branch at the curve was reduced and trimmed. Once this was done, Hugh could start to refine by taking some height out of the top. At this point, he is responding to the straight section but may look to change this later. To maximise the line, Hugh looks at various angles and settles on the tree being tipped. Next a decision had to be made about direction, as this tree had branches which were both falling downwards as well as rising up. Hugh kept the top and the up/down movement on each side. Casuarinas have a weeping appearance but structurally, they don’t weep.

Next, Hugh cleaned out the congested areas (rather like working a pine) so the lines are clear before starting wiring. Decisions about wiring made at the bottom influence choices made at the top so that’s where he starts. Casuarinas have fragile bark and so Hugh won’t over-wire. He approaches wiring Casuarinas with care, ensuring the wire is stable before a branch is wired. Fine wiring always goes back to a strong, solid bifurcation.

The branches are then set. The first branch was moving too far away from the trunk so Hugh moved it back towards the trunk to keep the flow. Now the two long branches are not necessary but Hugh is going to keep them until later so he shortened them for the time being. Finally he placed the remaining branches all around to occupy all the spaces. No pruning will be done until secondary branching is established.

When Hugh started this tree as a bonsai, he just focused on the lines and left the needles alone for twelve months after which all the needles had made branches. Next he defoliated it, wired it and laid out all the branches.This worked well as he had now set the structure. The tree was left for six months and then pruned, left again for six months and pruned again. It was finally used for a demonstration in the winter of 2018.

To encourage bifurcation (ramification), Hugh cut the branch where he wanted growth and multiple branches formed there. Once this was achieved and the lignification is formed, Hugh’s strategy changed and his aim was to now promote compact foliage. To do this, he takes all the needles on a branch between his fingers and gently twists. This causes the needles to break off with little damage and as a result, each segment forms a branch, one becomes forty! Hugh has then to pick and choose what he wanted to remain and remove the rest. There was so much density created that Hugh has pruned every three weeks throughout summer following the mantra ‘investigate, evaluate, eliminate’.